In ‘Involuted’ China, Eating Disorders Are a Hidden Epidemic

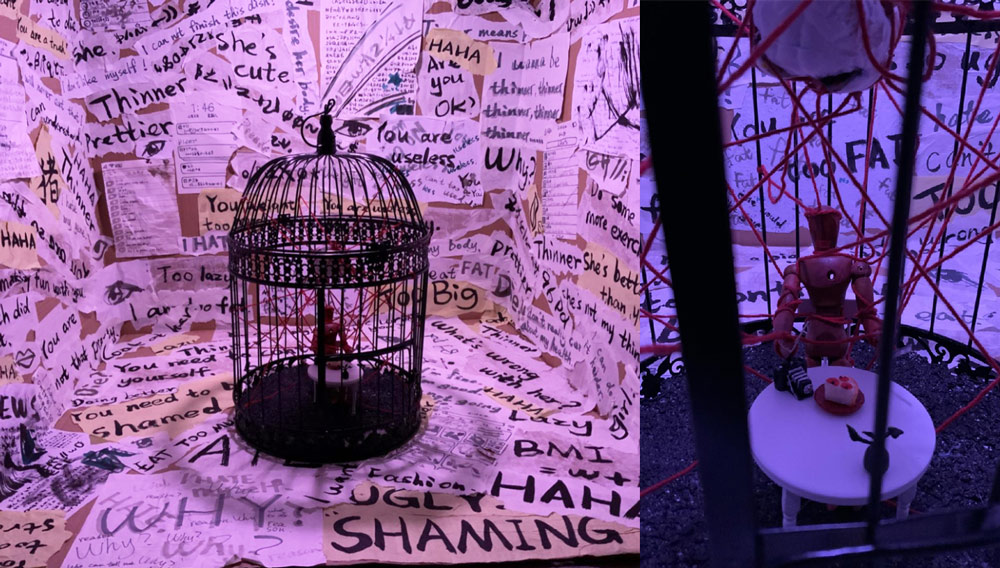

SHANGHAI — At the entrance to a packed gallery stands a female figure dressed in a pretty white dress. Her body is covered in abusive messages scrawled in red and black ink.

“You’re ugly,” “Your waist is too big,” “You look like a pig,” the notes read.

The artwork is part of a landmark exhibition in China titled “Anti Body-Shaming,” which opened in Shanghai on May 14.

Organized by a female advocacy group, it’s the first event to focus Chinese public attention on a frequently overlooked health crisis: an alarming rise in the number of girls and young women developing eating disorders.

Cases of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder have skyrocketed in recent years, with health experts placing blame on China’s social “involution” — or intense social competition — and toxic beauty standards that encourage extreme weight loss.

Just a few decades ago, eating disorders were extremely rare in China. Most people worked blue-collar jobs for low wages, and their main focus was putting food on the table, according to Chen Jue, director of the Eating Disorders Center at the Shanghai Mental Health Center.

But today, young Chinese face different pressures. Many aspire to a middle-class lifestyle, yet the competition for high-paying jobs is fierce. To make it, women often feel they need to have everything — not only the perfect grades, but the perfect figure, too.

“Nowadays, thinness is not only associated with beauty, but also with self-discipline, success, and even social class,” says Chen.

The rise of social media, meanwhile, has normalized extreme dieting and “size-zero” figures. Chinese influencers regularly take part in dubious “beauty challenges” — showing off waists tiny enough to hide behind a sheet of A4 paper, wrists under 4 centimeters thick, or deep collarbones capable of holding an egg.

Chen now regularly sees teenagers with severe anorexia and bulimia, who say they started wanting to lose weight because everyone at their school was constantly talking about dieting. Some female students skip lunch and eat only cucumber in the evenings, she says.

“It can’t be said that dieting will directly cause mental disorders,” says Chen. “But the cultural environment — the national focus on weight loss and the belief that thin is beautiful — has created fertile soil for people to develop eating disorders.”

Though eating disorders still only affect less than 0.1% of China’s population, according to a national mental health survey, there has been a dramatic rise in hospitalizations. In 2002, the Shanghai Mental Health Center received just eight visits related to eating disorders. By 2019, the number had jumped to over 2,700. As in other countries, the overwhelming majority of patients are female.

Eating disorders aren’t fatal in themselves, but they can lead to death. The most frequent causes are multiple organ failure due to malnutrition, or suicide. Nearly a quarter of people with a history of anorexia attempt to kill themselves, according to data published in the journal BMC Medicine.

Zhang, the curator of “Anti Body-Shaming,” knows firsthand how dangerous eating disorders can be. Like several young women who spoke with Sixth Tone, the 24-year-old began struggling with body dysmorphic disorder after she started university.

At high school, Zhang had been laser-focused on preparing for the gaokao, China’s notoriously tough college-entrance exam. But once she became a freshman in 2015, she found she had more free time. She started spending hours reading articles about how to get the perfect figure online.

Soon, Zhang decided she needed to go on a diet. At first, she just wanted to make her legs thinner, so she could “walk with confidence,” she tells Sixth Tone. She got an app to track how many calories she consumed.

The dieting was addictive. Before long, Zhang was eating one piece of fruit for breakfast, a small bowl of vegetables — which she repeatedly washed to remove any oil — for lunch, and nothing at all for dinner.

When her classmates said she was too skinny to be on a diet, she secretly hid food inside her sleeves and pockets to make it look like she’d finished her meal. By her sophomore year, Zhang’s weight had dropped from 50 kilograms to under 40, and she couldn’t stop.

“Even though I realized I was thin, I didn’t dare to eat,” she says.

Zhang’s hair began to fall out, her skin peeled, and she stopped having periods. Alarmed, her parents force-fed her cookies and milk. Zhang, however, continued to shed weight.

“It made me want to die when I ate,” she says. “A voice in my mind kept saying that food was the devil.”

In 2018, Zhang was finally admitted to an intensive care unit, by which time she weighed less than 29 kilograms. She was given a critical illness notice, and fed bottles of high-fat milk mixed with glucose to boost her weight.

In some countries, Zhang might have received treatment earlier. But in China, public awareness of eating disorders remains low, and the health system is still struggling to catch up with the rapid changes in society.

Until 2016, there were only two specialist centers for treating eating disorders in the entire country: the Shanghai Mental Health Center and Beijing’s Peking University Sixth Hospital.

Since then, a handful of other centers have opened, but the number of beds is still woefully inadequate. Between 2002 and 2012, the number of eating disorder patients at Peking University Sixth Hospital rose from around 20 to over 180. Ever since, it’s remained flat at just under 200, because the ward has hit peak capacity.

Parents, meanwhile, often have no understanding of what an eating disorder is. All too often, they dismiss their children as “abnormal” or “not self-disciplined,” and assume the problem can be fixed by forcing their kids to eat, health experts say.

When that doesn’t work, many parents — including Zhang’s — assume their child must have a physical, rather than psychiatric, condition. Chen says her patients have often spent years visiting all kinds of specialists — including gastroenterologists, gynecologists, cardiologists, and traditional Chinese medicine doctors — before finally arriving at her clinic.

In other cases, young women realize they have a problem, but are unable to access support due to China’s severe lack of trained counselors. Chinese universities usually have an onsite psychological center, but students often avoid them because the staff lack specialist training, a former student who previously had an eating disorder tells Sixth Tone.

“We laughed at it and thought it was useless,” says the person, who requested anonymity for privacy reasons, about her college’s psychological center.

Young Chinese like Zhang, however, are determined to change things. Though only the government can fix the shortage of health care resources, they can at least make society more aware of the dangers of eating disorders, and encourage those struggling to seek help.

The “Anti Body-Shaming” exhibition is part of this movement. For the event, Zhang worked with nearly 30 artists, most of whom had struggled with eating disorders in the past. They filled the gallery with paintings, installations, and poetry expressing the psychological pain caused by their conditions.

“We aim to show the public the inner world of body anxiety and eating disorders,” says Zhang. “They can experience our whole psychological journey.”

The event wasn’t only intended to shock, but also to heal. Halfway through the opening day, Zhang and her collaborators marched through the gallery wearing white veils and holding red roses.

Standing among the artwork, eyes closed, the women performed a “self-marriage ceremony” — pledging to love and cherish themselves for the rest of their lives. Some of the brides smiled with joy, while others wept quietly.

Zhang says the stunt was an attempt to send a message to girls across China: It’s OK to accept themselves as they are.

“We want to call on people to give themselves the gentlest and most unreserved love,” says Zhang. “They should embrace their imperfections.”

The message has a particular urgency in China. Though women are starting to push back against toxic beauty standards, the body positivity movement is still in its infancy in the country.

But embracing imperfection is about more than combatting girls’ negative body images, Zhang says. It’s also about countering China’s relentless culture of competition, which sees kids cram for high-pressure exams from primary school onward.

In Chen’s experience, patients with eating disorders tend to have similar characteristics. They’re often sensitive, have low self-esteem, and are overly self-critical — even when they’re already highly successful.

“They firmly believe in setting goals for themselves, then working hard to achieve them,” says Chen. “Then, it spirals out of control.”

He Yi believes her obsession with success was a major factor behind her eating disorder. The 32-year-old tells Sixth Tone she developed bulimia when she was just 17 — again, soon after starting college.

All through her childhood, He’s self-esteem was based on her performance at school. For her, good grades equaled success. But at university, she started to feel there were other obstacles to her achieving her goals.

“Advertisements, movies, and novels all told me that successful women should have control over their bodies,” says He, who used a pseudonym for privacy reasons. “I felt I could succeed by getting thinner, so I went on an extreme diet.”

For the next seven years, He suffered repeated bouts of binge-eating and forced vomiting. Sometimes, the cycle repeated three or four times a day.

At the time, public awareness of eating disorders was even lower in China than it is today, and He didn’t tell anyone about her condition for years. She considered herself a monster.

“I thought I was the only person in the world who’d do such disgusting things to food,” says He. “I was afraid if I told anyone, they wouldn’t want to be my friend anymore.”

Afraid of seeing a doctor, He bought some self-help books. These appeared to help, and over time her binge-eating and purging decreased. Now, she’s doing what she can to help other people experiencing similar problems.

“I thought it was difficult to find a suitable counselor in China, so I had the idea of becoming a mental health professional myself,” she says.

At 27, He went to the U.S. to study clinical social work. She also founded an online platform for people with eating disorders, which now has nearly 30,000 followers in China.

According to He, around 88% of her subscribers are female, and 42% are between 18 and 25 years old. Connecting with others on the platform has become an important part of her life.

“Having an eating disorder made me feel very lonely,” says He. “I won’t be able to maintain my recovery if I’m isolated.”

Chen, the psychiatrist, is taking a wider view. She believes to help children with eating disorders, clinicians first need to change the attitudes of their parents.

Chinese parents still often prioritize their kids’ academic performance, rather than their mental health, Chen says. At the Shanghai Mental Health Center, she sees parents rush to discharge their children as soon as they show a slight improvement, worried the child will fall behind at school.

“There are also children who come to the hospital with textbooks and do homework during their treatment,” Chen adds.

Altering these deeply held beliefs will take time, but Chen and her team are doing what they can. They have designed a special treatment program for China. The family-based therapy lasts up to 12 weeks, and focuses on educating the family members of people with eating disorders, especially parents.

“Educate the parents, change their minds,” says Chen. “Then, their children with eating disorders will gradually gain a sense of security, which will help their recovery.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.